The empire fights for coal and iron, but the Hron fight for their way of life…

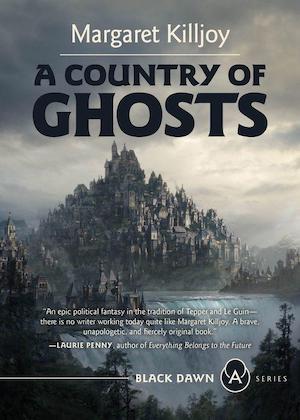

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Margaret Killjoy’s A Country of Ghosts—available from AK Press.

Dimos Horacki is a Borolian journalist and a cynical patriot, his muckraking days behind him. But when his newspaper ships him to the front, he’s embedded in the Imperial Army and the reality of colonial expansion is laid bare before him.

His adventures take him from villages and homesteads to the great refugee city of Hronople, built of glass, steel, and stone, all while a war rages around him.

The empire fights for coal and iron, but the anarchists of Hron fight for their way of life.

“The Man Beneath the Top Hat” is what I thought I was going to call the series, back when the editors of the Borol Review first assigned it to me. Forty, maybe fifty column inches a week for six months on Dolan Wilder, “the man who conquered Vorronia.” Dolan Wilder, the enigmatic young upstart of His Majesty’s Imperial Army, famous for his bold, ride-at-the-front-of-the-charge style. The man who put more square miles under the gold-and-green than anyone had in a century.

I was all set to write about his rough-shaven face, his black locks, his fine taste in brandy, and the soft touch he had for granting quarter to conquered foes. I was told at least two column inches were reserved for his gruff-but-friendly tone. I was to write about a cold, stony man who nursed a tender heart that beat only for service, only for the King, only for the glory of the Borolian Empire.

Buy the Book

A Country of Ghosts

Instead, though, I saw him die. But no matter, that—he bore few of those traits I’d been told to ascribe to him, and bore none of them well. Instead I write to you of Sorros Ralm, a simple militiaman, and of the country of Hron. And it seems you won’t find my report in the Review.

For a writer of my adventurous temperament and immodest ambition, it was a dream assignment. I can’t tell you I wasn’t elated when Mr. Sabon, my editor, called me into his smokey office and told me I’d been sent to the front, to be embedded in Wilder’s honor guard. “I’ll be honest with you, Dimos,” Mr. Sabon said to me, breathing shallow in that strange, wounded way of his, “you’re not getting this job because we think you’re the best. You’re not. You’re getting this job because it’s important but dangerous, and you’re the best writer we can afford to lose.”

“I understand,” I replied, because I did. My middling place in the stable of writers had been made clear to me near-daily since my demotion.

“I know you like to tell the truth,” he continued. “You’re an honest man. And that’s fine—we’re an honest paper. But I don’t want you stirring anything up just for the sake of stirring it up.”

“I understand,” I said.

“I mean it. Look me in the eye and tell me all that’s behind you.”

“It is,” I said. And at the time, I’m pretty sure I meant it.

“Good,” he said. “Because this is an important assignment, real important. You do this, and everyone in this city is going to know your name.”

That much, at least, was true.

I walked out of his office with my head held as high as my spirits, floated down the stairs, and returned to my desk in the pool of hacks. I put on my bowler and coat and walked out of that building and onto the streets of Borol, the low winter sun failing as always to bring even a hint of warmth through the chill fog that rolled off the bay and stunk of industry.

I took more mind of the city that day than most, knowing I was soon to depart. I was off to the savage wilds, to the very edge of empire and civilization, to leave behind the comforts and sanity of His Majesty’s capital city. Not ten feet from the door, I tripped over an urchin girl passed out from hunger or vice.

I know most of my readers will be well-acquainted with the conditions of the working and middle class of Borol, so I won’t linger too long on the details of that walk, but I hope you will indulge me a bit as it serves such an amazing contrast to Hron, to the world I did not yet know I was off to see.

My walk took me through the docks and their attendant horrors of press gangs and bribed officials, through the meatpacking district and the human screams that were so often indistinguishable from the death cries of slaughtered beasts. I walked through Strawmarak Square, where the nobility and merchant houses attend theatre, defended from the protestations of the poor by means of policemen with sticks and guns. I walked the edge of Royal Park, where, scattered among the birch groves, were the lot who’d been left with little to sell but sex and had nowhere safe to do so. I walked past men at work and men without work, past children playing games like “nick a wallet or you won’t eat tonight,” past barkers and buskers and scavengers and skips, past cripples and beggars and whores, past dandies and gang fights, past lamentations and sorrow and the strange joy one finds in the daftest of places.

In short, I walked through Borol. And I didn’t suppose I would miss it.

Truth be told, it was to be my first time off the peninsula. I’d been a reporter for five of the twenty-three years I’d been alive, but here’s how colonial reporting was done at the Review: I sat at a desk and read Morse code off the wire. Sure, I spoke four languages, and sure, I took raw data and used it to write what I hoped were compelling, informative narratives, but there was a reason they called us hacks. Nearly all of our foreign correspondents were rather domestic.

The Chamber of Expansion itself was underwriting the story on Wilder, so I had an economy cabin aboard the HMR Tores, a double-wide luxury train that ran the overland route to the mainland. It was the long way to Vorronia, to be sure, but the Council had provided me with no small amount of reading material and the extra few days gave me time to pour through the tens of thousands of words already put into ink regarding the exploits of our hero Wilder.

I spent the hour of daylight that remained watching as the famous idyll of the Borolian countryside swept past my window, then turned my attentions to the task before me.

“Our country is in peril,” my assignment from the Council began. “Popular support for expansionist policy is flagging, leaving us vulnerable.”

The council went on to explain that, ever since Vorronia had acquiesced to our rule and signed the Sotosi Treaty, recruitment had been down. There was a whole page about how the Cerrac mountains were rich with iron and coal, and a second about how it was our duty to bring the fruits of civilization to the few scattered villages and towns in the area. What the country needed was a hero to inspire recruitment, the Council explained, a hero like Wilder.

“The Man Beneath the Top Hat” was born in poverty and dragged himself out of the mire with hard work, patriotism, and a gravely voice that demanded respect, reaching the rank of General Armsman by force of will and valor alone. And I had three thick books in my luggage that could prove it.

It’s hard to remember how I’d felt about the assignment at the time. I’d like to say I’d known it was all so much horseshit. I’d written probably a thousand column inches in the Review about the conditions that the majority of Borolians lived in, back before they put me to staffing the wire, and I didn’t think the Vorronian war had done anything for them but killed those fool enough to enlist or unlucky enough to be conscripted. Victory, unsurprisingly enough, hadn’t brought a one of the corpses back to life.

But I admit that I’d probably thought this was different. We weren’t fighting a war, we were colonizing the mountains. We were guaranteeing the country access to resources.

And it wasn’t my job to editorialize. I’d tried that once, had maybe oversimplified some things, and I’d seen with my own eyes the damage self-righteous reporting can wreak. So I didn’t think it was my place as a journalist to question the story itself, the story that ran all the way to the roots of the Empire. I didn’t question the story that of course we had a king, that of course we obeyed the Chambers and their attendant police. Of course we worked for the expansion of imaginary lines, of course we let industrialists amass wealth.

So I was probably just excited to have been given such an important assignment.

In a war between armies, like the Vorronian war that Borolia so recently won, the “front” is a dynamic, but tangible, geography. It exists. Though inadvisable, one can stand on it or cross it. Armies wait in barracks or trenches or repurposed city buildings and fire guns at one another like gentlemen (or gentlewomen in the Vorronian case, as that culture historically lacks the Borolian censure of women combatants).

But the new war was against territories and not nations, against peoples and not armies. The front in a war like that is amorphous, and from talking to soldiers, it’s largely a state of mind. To be at the front means to be ready for battle.

At the time I was sent out, no one even knew the country of Hron existed. The Cerracs were just a territory to be conquered and colonized, with only a handful of villages and towns to speak of. The snow-capped mountains were just to be an eastern wall for the empire, butting up against Ora. The Imperial forces expected little resistance. Thankfully, they were wrong.

Excerpted from A Country of Ghosts, copyright © 2021 by Margaret Killjoy.